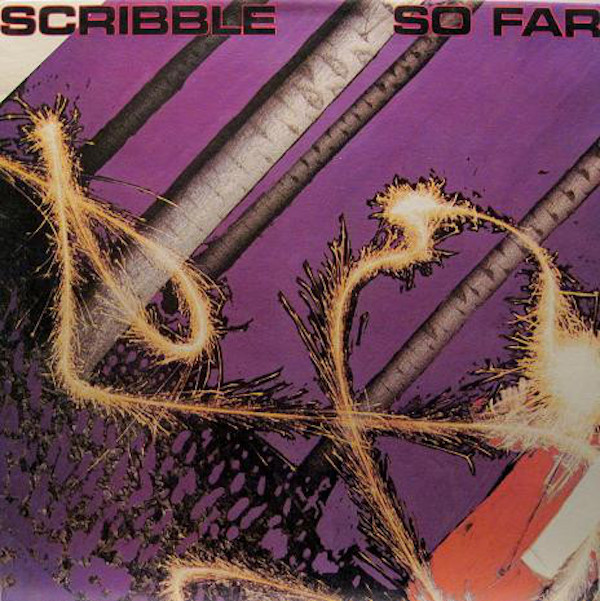

Scribble was a short-lived project of Australian musician and songwriter Johanna Pigott, formerly of punk band XL Capris. Acting as lead vocalist, guitarist, pianist, keyboardist, songwriter, and producer, Pigott recruited her partner Todd Hunter for bass and keyboards, as well as a slew of session musicians. She eventually dissolved Scribble to focus more on her writing, and went on to rack up many songwriting and screenwriting credits, including Keith Urban’s first single, “Only You,” which is unsurprising given how good it is (also he looks confusingly hot in this admittedly blurry video? I regret none of these opinions). Though Scribble has garnered a little bit of cult interest, it never received much critical acclaim that I would argue this record most certainly deserves.

Scribble was a short-lived project of Australian musician and songwriter Johanna Pigott, formerly of punk band XL Capris. Acting as lead vocalist, guitarist, pianist, keyboardist, songwriter, and producer, Pigott recruited her partner Todd Hunter for bass and keyboards, as well as a slew of session musicians. She eventually dissolved Scribble to focus more on her writing, and went on to rack up many songwriting and screenwriting credits, including Keith Urban’s first single, “Only You,” which is unsurprising given how good it is (also he looks confusingly hot in this admittedly blurry video? I regret none of these opinions). Though Scribble has garnered a little bit of cult interest, it never received much critical acclaim that I would argue this record most certainly deserves.

Prim, elegant sophisti-pop tinged with post punk and new wave. Opener “It’s Blue” is such a pleasurable, effortless piece of guitar pop that it feels like taking a hot bath and is a big part of why I’ve had this record on repeat for the past few weeks. Elsewhere, find Pigott’s opiated, smoky, slow-jazz take on “The Lady Is A Tramp,” bombastic brassy new wave on “Adaptability,” and an absolutely sublime cover of Roxy Music’s “Mother Of Pearl,” which, despite being eight minutes long, always makes me wish it were longer. An ideal wintertime record that feels more and more like a favorite sweater with each listen. Thank you Flo for bringing me here via this excellent mix :}

Category: Album

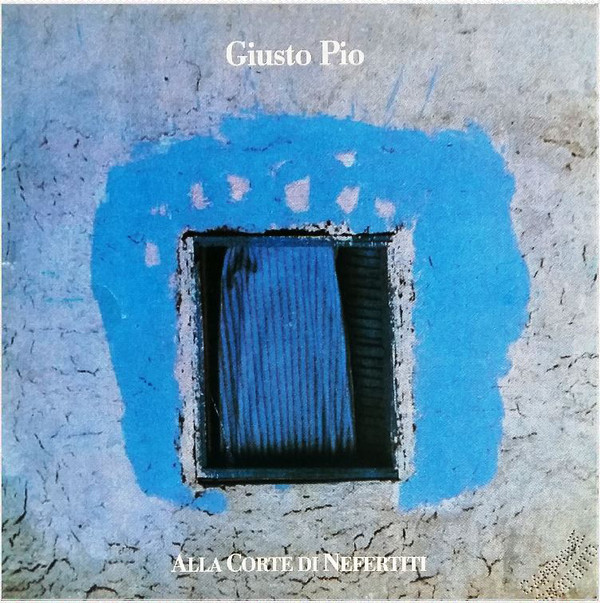

Giusto Pio – Alla Corte di Nefertiti, 1988

Pristine minimal ambience from Italian musical giant Giusto Pio. Best known for his many collaborations with Franco Battiato, Pio was a composer and world class classical violinist born in Castelfranco Veneto in 1926. He was sought out by Battiato as a violin teacher, but the two went on to sculpt Battiato’s sound from post-prog to minimalism to Europop, with many other projects along the way, like their contributions to this Francesco Messina record. Among these collaborations, Battiato produced Pio’s first solo album, considered to be Pio’s crowning achievement and a holy grail of avant-garde minimalism: 1979’s Motore Immobile. Pio continued to release solo records until 1995. He passed away in 2017 at the age of 91.

Alla Corte di Nefertiti, however, is a very different beast. Though it was released by Battiato’s publishing company L’Ottava S.r.l. as a subsidiary of EMI Records, Battiatio wasn’t involved in production. The record is two long-form tracks of synth impressions, the first of which is more of a holistic composition and the second of which is a reflection, or “frammenti,” of the first, sonic pieces broken up and scattered with spaces falling where they may. I like the more pure minimalist moments the best, where single vibrating tones are left to hang in the air like washes of color, but there are also some great moments with synthetic choirs of angels radiating concern from plastic celestial bodies. A few moments of percussive texture, some which have a cinematic urgency that feels appropriate for Pio’s background, but for the most part Alla Corte di Nefertiti is just drifting in pillows of sound. Made on an Akai MG1212. Excellent for working to, or waking up to. Thanks for all the music, Giusto.

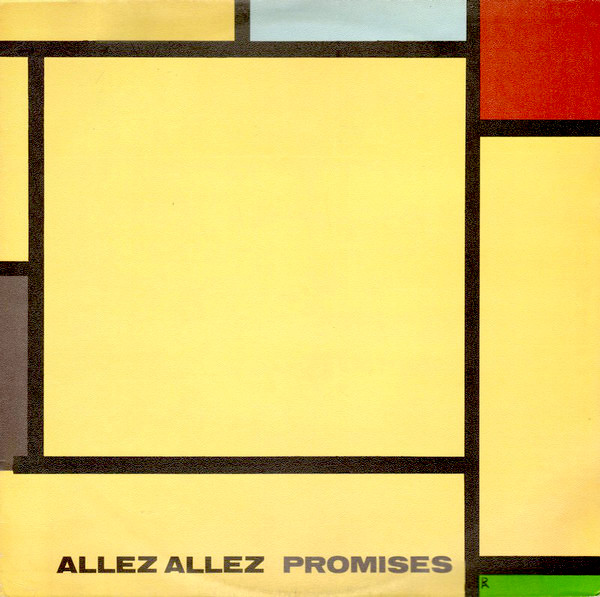

Allez Allez – Promises, 1982

Ridiculously catchy Belgian new wave disco-funk. Bombastic, soulful vocals from Sarah Osborne; Martyn Ware production, of course. Not too much to say about this other than that it fills a dance floor very quickly. Good for fans of Liquid Liquid, ESG, Lizzy Mercier Descloux. I’m also including a bonus b-side from the single for “Valley of the Kings” called “Wrap Your Legs (Around Your Head)” which, uh, really slaps.

Hoedh – Hymnvs, 1990

Peak dark ambient. The first of two solo records from German trance and ambient musician Thorn Hoedh, who passed away in 2003. Equally lauded as a holy grail of the genre and bemoaned as an overlooked masterpiece, Hymnvs manages to be both sprawling and claustrophobic; cinematic and lo-fi; inorganic and classical. If you’re not paying attention, these seven long-form tracks (or hymns) might appear like a flat and unchanging expanse of black tones, but a few seconds in headphones proves otherwise–there’s actually a great deal of intricate movement happening beneath the surface, so much so that tracks like “Das Geistige Universum” seem to actually evoke the nausea of being pitched around in a boat in choppy water. Elsewhere, ringing overtones and expansive, bending pitches, as on “Hoedh (Sonnenklang)” are completely sonically disorienting. There is, in short, a lot going on here.

I love the anonymity of the instrumentation–it’s frequently unclear whether we’re listening to an acoustic instrument that’s been modified, or to a synthetic interpretation of an instrument. Still, the sounds are warped around the edges in familiar ways: “Heilige (Mantra Der Rotation)” has the gape of wind instruments in a massive tunnel; other tracks feature synthetic remnants of strings, piano, horns; but always we feel a certain kind of crackling closeness that can’t simply be attributed to lo-fi production (though there is a distinct feeling of of well-worn vinyl). It’s as if the sounds have had tiny shading details painted onto them by very meticulous hands.

It seems as if listeners have consistently ascribed a deep and impenetrable melancholy to Hymnvs, and it’s true that it imparts a feeling of descent, or even of disassociation. But if listening to this record is the sensation of slowly sinking backwards into water while looking up at the receding surface, then inevitably there are beams of light penetrating the surface, sun-dappled and speckled with dust motes, which is to say that Hymnvs is flecked with joy, with optimism, as the best hymns are. For fans of The Caretaker, Gavin Bryars, William Basinski, or, uh, Wagner.

Nancy Priddy – You’ve Come This Way Before, 1968

One-off psych-folk record from musician-actress-model Nancy Priddy. As I understand it, her label dropped the ball on promotion, and though I imagine 1968 audiences would have been very enthusiastic about an experimental psych-folk-pop album with lush instrumentation, tasteful application of distortion, and girl-group inflections, the record never made it very far into the world. Since then it’s become a quiet collector favorite, and it’ll only take you a few seconds to appreciate why.

The range of moods, textures, and vocal personas that Priddy, who co-wrote the whole thing, touches in the span of just over half an hour is remarkable. It’s perhaps most clearly embodied in the shapeshifting “Mystic Lady,” which turns tonal corners with surprising speed and yet still feels utterly seamless, moving between psych folk balladry, sunshine pop, baroque horns, and a particularly good gospel-soul breakdown finisher. It sounds like enough to give you sonic whiplash, but Priddy carries it impressively well, especially considering that this was the only full-length she ever made. (She had previously recorded backing vocals for Songs of Leonard Cohen, and went on to cut a single with Harry Nilsson and contribute to Mort Garson’s Signs of the Zodiac, but effectively retired from music shortly thereafter to continue her acting career.)

I love that none of these songs are love songs, at least as far as I can tell. I also love the flexibility of Priddy’s voice–my favorite mode of hers is quietly salty, slinging words around with a touch of unamused thorniness as on opener “You’ve Come This Way Before.” Elsewhere, she veers into sultry Judy Garland-esque jazz vibrato, ethereal straight tone, and yé-yé-esque coyess. Her implementation of vocal harmonies–presumably some of which include backing vocalists, though I’m unable to find their names anywhere–is gorgeous. Perfect production by Phil Ramone. A real powerhouse of a record. Good for fans of Honey Ltd., Dusty Springfield, Jefferson Airplane. Listen in headphones if you can. Enjoy!

Doji Morita – A Boy ボーイ, 1977

Gossamer folk ballads and cinematic string arrangements from musician, singer, and songwriter Doji Morita (stage name). Born in Tokyo, Morita-san began her musical career after the death of a friend, and made seven records in the span of her eight year long musical career. An intensely private person, Morita-san chose not to perform often or in large venues, and though she was signed to major labels, she avoided exposure and increased commercialization wherever possible. She wore a wig and sunglasses in most photos and live appearances, and eventually stepped away from music completely to focus on her domestic life. Sadly, she passed away a few months ago at the age of 65.

The records of hers that I’ve spent time with, such as the also excellent スカイ = きみは悲しみの青い空をひとりで飛べるか (Mother Sky), are all colored by her intense melancholy and nostalgia, and A Boy ボーイ is no exception. Spanish guitar, swelling and cinematic string arrangements, and hushed, forlorn vocals. I imagine that in addition to her folk contemporaries, Morita-san was heavily inspired by Brazilian, Portuguese, and even Cape Verdean musical traditions, with a lot of her instrumentation, vocal lines, and vocal inflections strongly suggesting morno (though she also nods to American folk and country in “君と淋しい風になる,” before submerging us in another particularly dramatic bath of strings). I suspect she was an Ennio Morricone fan as well.

Interestingly, at several points throughout the record songs cut off abruptly and are followed by snippets of what I assume are field recordings–the flapping of a bird’s wings, or rushing water. It’s a motif that appears on her other records, too, and I’d imagine it’s a textural nod to her interest in baroque folk and pastorality. This is a high drama and high reward record, and feels peak autumnal to me, so I hope you enjoy it.

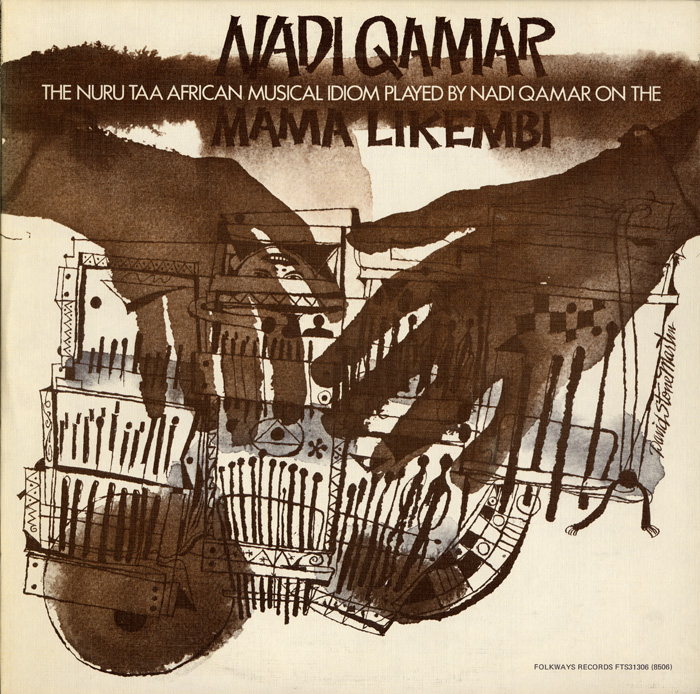

Nadi Qamar – The Nuru Taa African Musical Idiom Played By Nadi Qamar On The Mama Likembi, 1975

A record comprised entirely of mama likembi, a homemade instrument consisting of a grouping of African thumb pianos (aka likembe, mbira, or kalimba), meant to be played with the fingers rather than the thumbs. Before his conversion to Islam, Nadi Qamar was known professionally as Spaulding Givens, and you may know him as a revered jazz pianist and composer. Born in Cincinnati in 1917, of “Seminole, Cherokee, and African heritage,” he recorded extensively with Mingus in the early 50s and performed with Max Roach, Charlie Parker, Oscar Pettiford, Lucky Thompson, and Buddy Collette. His later career saw him focused on African instrumentation and ethnomusicology: he produced several large-scale performances of his own compositions, toured with Nina Simone, taught voice, piano, and orchestra at Bennington for seven years, and made a series of mama likembi records for Folkways,* some of which are highly instructional and technical audio guides.

The Nuru Taa African Musical Idiom is gorgeous. Under deft hands, Qamar’s mama likembi sounds like a harp, a classical guitar, a koto, and still like itself. Cloaked in a thick layer of roomtone, these recordings feel just as small and intimate as one might hope. You can hear she shifting of Qamar’s clothing, hear his hands brushing up against wood. And you can hear him shifting in and out of different tunings, “draw[ing] from many sources to project a contemporary Black expression,” as he writes in the liner notes. Though Qamar’s interest in music’s spiritual potential is plain, this is shy, discreet music, ideal for background music while working or even for meditation. It’s also excellent music to hole yourself up indoors with when it’s suddenly very cold outside.

*If you’re unfamiliar with Folkways, it’s a terrific catalogue to sift through if you have a free afternoon or ten. It was founded in 1948 to document “music, spoken word, and sounds from around the world” and was acquired by the Smithsonian Institute in 1987. Since then, the Smithsonian has kept all of their 2000+ titles available on their website.

Jane Siberry – No Borders Here, 1984

Guest post by Nick Zanca (Quiet Friend / Mister Lies)

We don’t talk enough about the potential of the pop LP, as a form, to construct a kind of auditory theatre. Hounds Of Love, Big Science, Hejira, A Wizard A True Star, Jordan: The Comeback (which I’ve written about here before), more recently Blonde and Blood Bitch–these are records that build distinct sound-worlds track to track, display personalities so disparate, observations so tart, that you’re quick to forget they’re all coming from the same voice. And yet, the cohesion (where does it come from?) still exists.

For all intents and purposes, Jane Siberry’s sophomore LP No Borders Here is such a record. The title tells you everything you need to know before you press play–here she is acerbic, energetic, anxious, socially awkward and beguiled by the people she encounters with the same eye for detail present in Rousseau’s jungles. We step-ball-change between time signatures and synth flourishes as quickly as we shift perspectives from deluded waitresses to enigmatic dance class partners. The storytelling feels like the work of someone too well in tune with the anxiety of urban dwelling (in her case, Toronto) but also able to escape it. For the gearheads reading, you’re not going to find more advanced LinnDrum or Fairlight programming on a record marketed as “new wave.” You’re just not. Sorry.

I could go on about the thickness of the sound palette here, but I don’t want to give the game away, so I’ll end with a quote from Renata Adler’s Speedboat–what I feel to be this record’s literary spiritual sister–that I think sums it all up:

Speech, tennis, music, skiing, manners, love – you try them waking and perhaps balk at the jump, and then you’re over. You’ve caught the rhythm of them once and for all, in your sleep at night. The city, of course, can wreck it. So much insomnia. So many rhythms collide. The salesgirl, the landlord, the guests, the bystanders, sixteen varieties of social circumstance in a day. Everyone has the power to call your whole life into question here. Too many people have access to your state of mind.

Give this a front-to-back listen like you would for any of the aforementioned records, and then go watch this tour documentary and revel in how beautifully she presents this record in a live context (those headset mics! those backup singers!). I’ve seen Jen write this a lot, but it bears repeating here: if this record is for you, it’s definitely for you.

Robbie Băsho – Visions Of The Country, 1978

Apologies for a few weeks of silence–I fractured a finger in a bike accident recently, and while I’m happy to be otherwise unscathed it’s made typing a nuisance. I’ve also been feeling so depleted by and sad about our ongoing Supreme Court drama that I haven’t had it in me to think about much else. But, it’s fall, which means I’m listening to Robbie Băsho, and maybe you should too.

Though Băsho’s life was tragically cut short by a freak chiropractic accident, he accomplished so much in his twenty years of making music and left us an impressive catalogue to celebrate. He went to military school, then pre-med. He painted, sang, played trumpet, played lacrosse, lifted weights, wrote poetry, and changed his name to Băsho after the Japanese poet. He went through phases of cultural and musical obsession, including Sufi, Buddhist, Hindu, Japanese, Indian classical, Iranian, Native American, English and Appalachian folk, Western blues, and Western classical “periods.” He “used open C and more exotic tunings and he developed an esoteric doctrine for 12- and 6-string guitar, concerned with color and mood. He spoke of ‘Zen-Buddhist-Cowboy songs’ a long time before Gram Parsons mentioned his vision of Cosmic American music.” He studied under Ali Akbar Khan. He pushed for a broader appreciation of the steel-string guitar as a classical concert instrument. He made 14 studio albums in 19 years. He wrote “a Sufi symphony” and another for piano and orchestra about Spanish and Christian cultures coming to America. He’s considered one of the geniuses of American folk and blues, and yet his name often gets lost in conversations about John Fahey, Leo Kottke, and Sandy Bull.

Visions Of The Country was recorded at what was arguably the peak of his musical power, two years before he played the concert recorded in Bonn Ist Supreme (you’ll notice some of these songs show up there as well). It’s a sprawling love song to America, and it seems to exist fully outside of 1978, with Băsho’s voice and sensibility looking both backwards, to early Americana folk and blues; and forward, with his explicit borrowing from global music traditions. He contributes some gorgeous whistling, most notably on “Leaf In The Wind,” and his whistle is every bit as theremin-like and expressive as his singing voice would suggest.

This is a potentially blasphemous thing to say about such a singular guitarist, but my personal standout is “Orphan’s Lament,” which features only Băsho accompanying his signature quaver on a slightly out-of-tune piano being played with the kind of abandon you might expect to hear after a few drinks. I love that the piano part alternates between a very pastoral folk melody and sounding almost like a hammered dulcimer. His voice is at its most brutally effective and emotively pure here, which is to say, blast this in headphones if you want to do some real ugly crying: “Born for love and nothing more/Given away cause we was poor/Will you wait, will you wait for me?” Băsho himself was orphaned as a baby, and the liner notes dedicate this song as follows: “To all the little orphans of the rainbow; and may they find the gentle hand of the Creator.”

Still, though he gives airtime to piano, strings, voice, and whistle, he never lets us forget what he can do with a guitar. I love that Visions of the Country houses a few bare bones guitar parts that feel more in line with what a 2018 audience might associate with “folk music”–“Blue Crystal Fire,” for example, could hardly be more simple, and yet it’s broken wide open by, yet again, that plaintive and tremulous voice. Elsewhere, we hear more classic Băsho guitar construction: long builds of dazzling finger picking with big, cascading crescendoes, and always so much warmth. I’m reminded of his assertion that nylon-string guitars were suitable for “love songs,” but that steel-string guitars could communicate “fire.”

Take this for an afternoon walk if you’re able. I hope you enjoy it.

“My philosophy is quite simple: soul first, technique later; or, better to drink wine from the hands than water from a pretty cup. Of course the ultimate is wine from a pretty cup. Amen.”

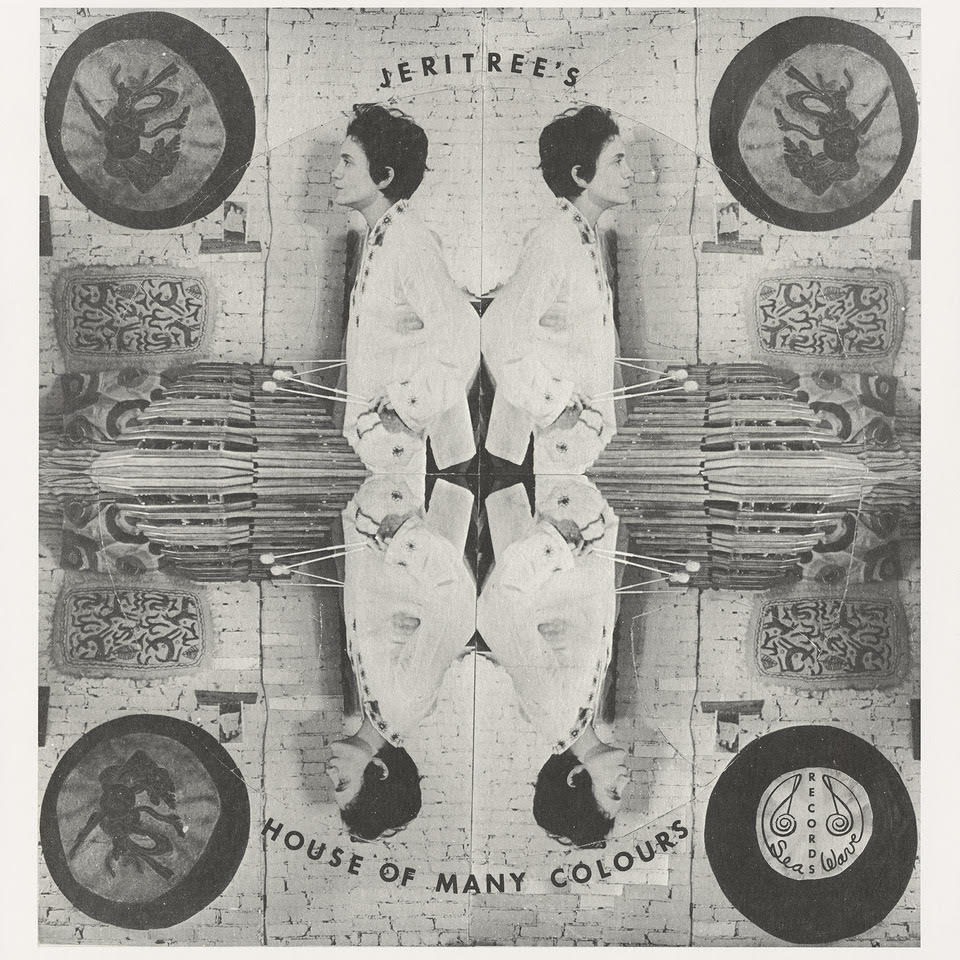

Jeritree – Jeritree’s House Of Many Colours, 1978