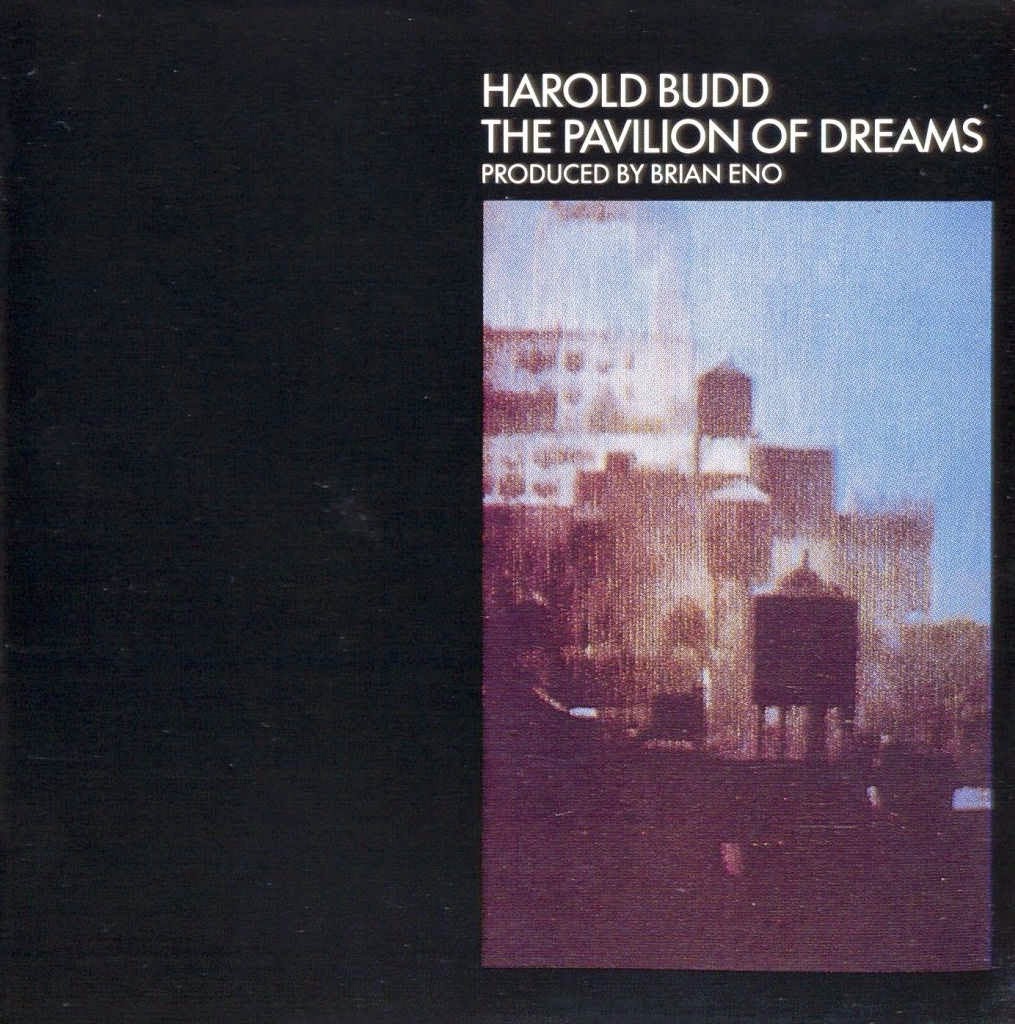

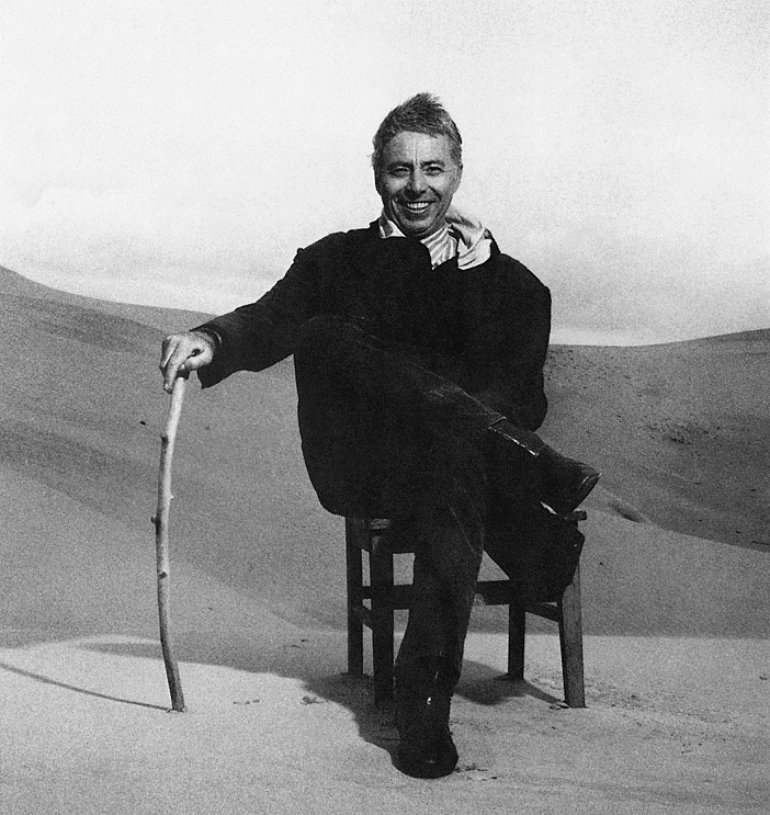

I wrote about this record in 2015, very briefly, and while I’m delighted by the opportunity to revisit it at greater length, I wish it was under different circumstances. Musician, composer, and poet Harold Budd passed away yesterday at the age of 84 from complications caused by COVID-19, and with him we have lost a giant.

It was jazz that first inspired musicianship in Budd, or, as he put it, it was “…Black culture that freed me from the stigmata of going nowhere in a hopeless culture.” He was drafted into the US army where he drummed in a regimental band alongside the highly influential free jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler. Budd repeatedly credited Ayler with granting him the freedom to abandon time signatures, a freedom which stayed with him throughout his career.

Budd was notoriously resistant to genre classifications, so much so that I feel a bit sheepish using genre tags on this post: “The word ‘ambient’ doesn’t ring a bell with me. It’s meant to mean something, but is, in fact, meaningless. My style is the only thing I can do well,” “When I hear the words New Age, I reach for my gun,” and, at greater length in this excellent 1986 interview:

I’ll tell you very frankly that this whole ‘new age’ business is very distasteful to me. I don’t like being even considered in that category and I have almost no respect for it at all. To me it’s a kind of arrogant philosophical point of view where music has a metaphysical or biological function. I agree that music has a metaphysical function but when that’s your whole point of view, when it isn’t just a thing that happens out of the normal course of events, I think it becomes arrogant and rather precious. It smacks to me very much of science fiction religion and that’s not me. It’s very lightweight and very bothersome to me. ‘New age music’ is a marketing ploy and I don’t think it has anything to do with the actual truth about the meaning of the music. The only thing that rings my bell is serious music and music is that way when it’s impossible to analyse: ‘new age music’ is easily analysed.

But new age or not, Budd’s music has a consistent quality of brushing up against an experience of the divine.

Perhaps part of his resistance to being labeled as “ambient”–a term which, by definition, suggests something incidental and negligible–is that much of his music isn’t actually optimal background music. (I would argue that the category of “music to fall asleep to,” which Budd is frequently cited as–presumably to his chagrin–is also not necessarily background music.) I’ll go ahead and plagiarize my 2014 post about The Moon and the Melodies, which Budd made in collaboration with Cocteau Twins and which began his decades-long collaboration with Robin Guthrie. While not all of these observations apply to Pavilion, there is most certainly a slipperiness and synergy that the two records share, as do many of Budd’s other works:

It’s an uncategorizable work, one which far exceeds the sum of its parts. It’s egoless. It’s a fluid, restless record, moody and aloof–it peaks several times, ecstatically, only to retreat back into itself. Startling synergy between these masterminds means that ambient and new age fans will find a lot to love here–it’s Harold Budd, after all, and there are long stretches of huge, hulking instrumental tracks. But the record is darker than typical new age–it feels like climbing through a cavernous skeleton, and the instrumental tracks (like “Memory Gongs”) are echoing and sometimes sinister. It’s not as effusive as Cocteau Twins, and perhaps not as immediately gratifying–many tracks fade out right when you want more the most. It’s not daytime music, and it’s not background music. Clocking in at just under 40 minutes, it’s a perfect on-repeat record, folding in on itself like water.

Budd began Pavilion in 1972 after returning from his “retirement from composing” with “Madrigals of the Rose Angel,” of which he said, “The entire aesthetic was an existential prettiness; not the Platonic τόκαλόν, but simply pretty: mindless, shallow, and utterly devastating.” Though the piece’s debut was at a Franciscan church in California conducted by Daniel Lentz (!), it was the piece’s subsequent live botching that led Budd to take up the piano in earnest in his mid-thirties:

Madrigals of the Rose Angel…was sent off for a public performance back East somewhere. I wasn’t there, but I got the tape and I was absolutely appalled at how they missed the whole idea. I told myself, ‘This is never going to happen again. From now on, I take full charge of any piano playing.’ That settled that.

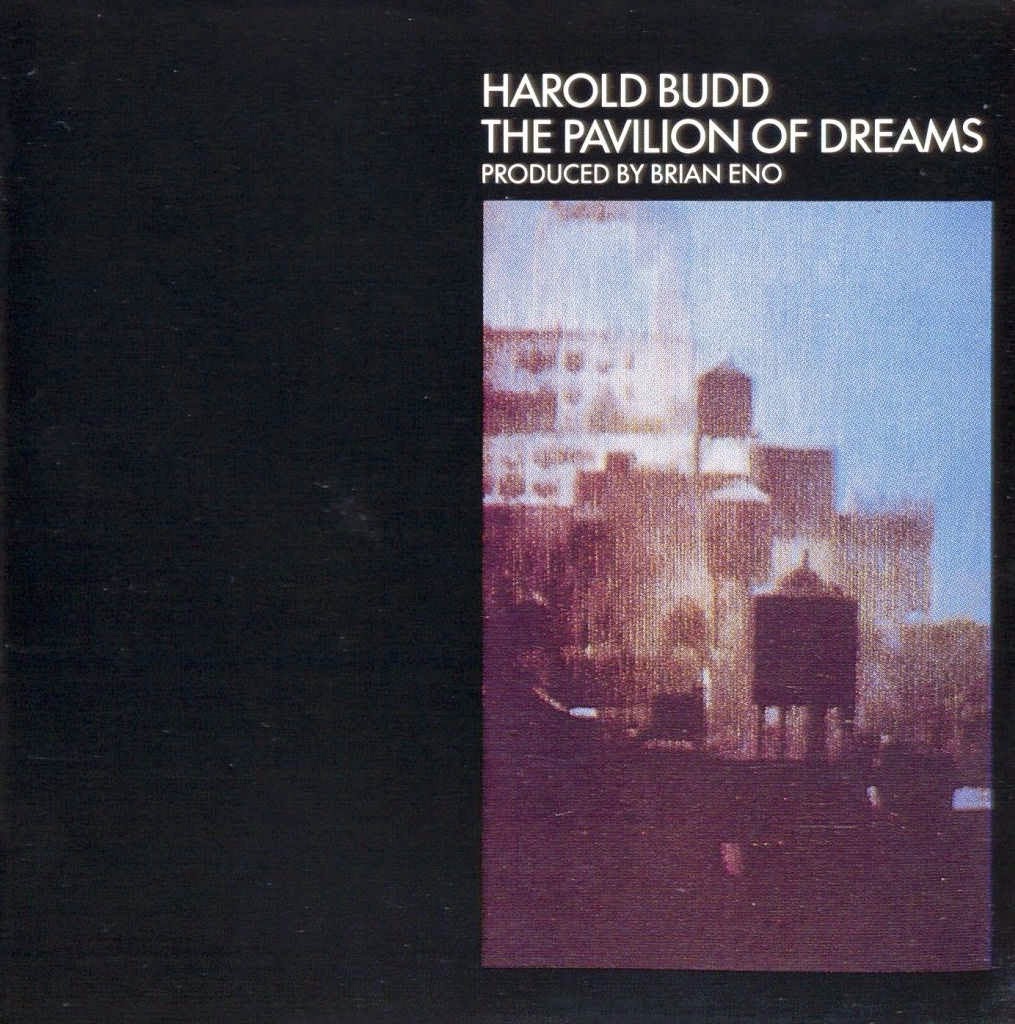

Here’s what I wrote about The Pavilion of Dreams back in 2015:

Twinkling, lazy jazz-scapes for new agers. A dripping, humid, reactionary piece of anti-avant-garde. Budd refers to this as his magna carta. Gavin Bryars on the glockenspiel and celesta, Michael Nyman on the marimba, Brian Eno production.

To this I’d like to add that I can think of few records which can so immediately shift the feeling of the room in which they are played in the way that Pavilion does, literally within seconds. It’s the sonic equivalent of taking a few deep, elongated breaths: the pulse slows, the jaw unclenches. It’s an opiated smoke drift in which, once again, everything Budd touches feels weighted with spiritual potency. The worldless, meandering glissandos sung by Lynda Richardson, though clearly delivered in a Western classical style, start to suggest Eastern devotional drone and chant traditions. The occasional chime from the glockenspiel begins to resemble bells used in meditation. And most thrillingly, at times you can hear the creak of the harp against the floor, the crack of a knee, the scrape of a chair. When music is this willfully shapeless, rolling through space like a liquid, it becomes that much more consequential to be reminded of solid objects, human bodies in a room. Everything becomes sacred. Perhaps this is what Budd was after with his commitment to “existential prettiness” at the deliberate expense of meaning. Perhaps this is why critics and listeners still can’t help but try to pin him down with a label: it’s difficult to hear this much reverence without trying to name it in service of something.

Goodnight Harold, and thank you for everything.