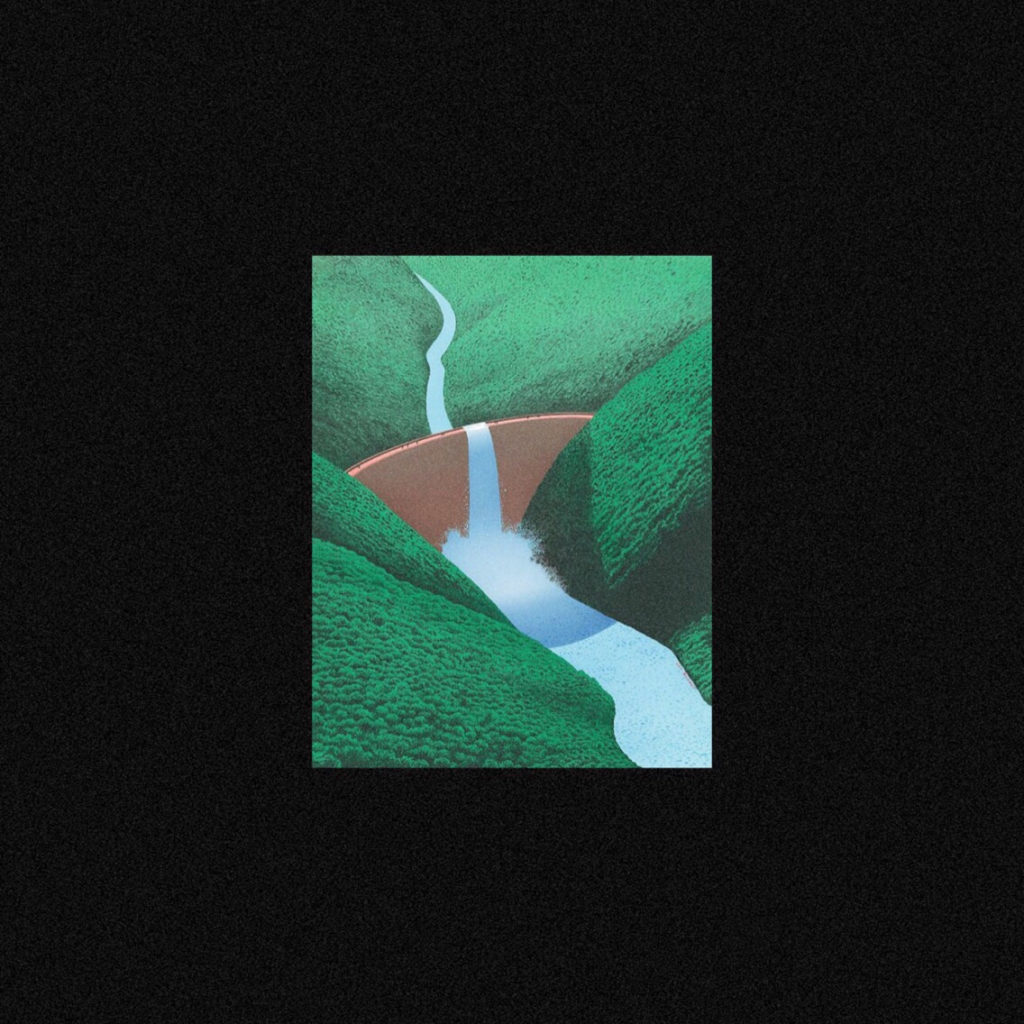

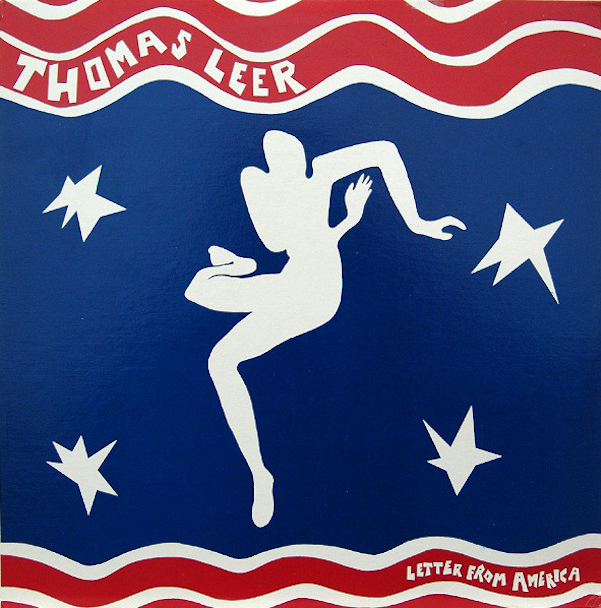

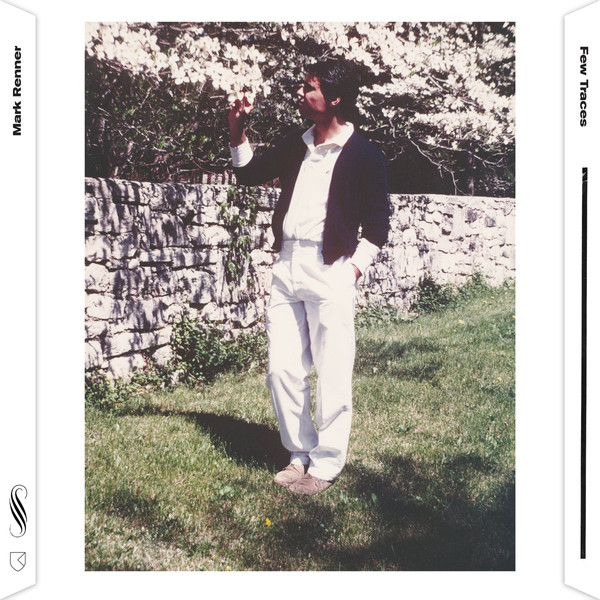

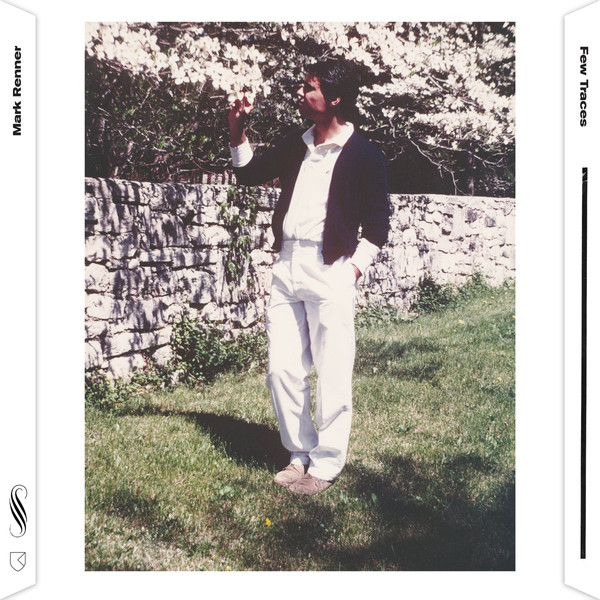

Mark Renner first encountered punk as a teenager in Upperco, a country town in rural Maryland. Growing up on his family farm, he became a young acolyte of the British exports hitting not-so-distant Baltimore record store shelves in the late 70s, and was baited by an area musician-wanted ad declaring Ultravox a primary touchstone. This nascent band and a pair of other group experiments flamed out, and in their ashes Renner began recording independently around 1983 with a portable 4-track, electric guitar, and classic Casio CZ101 synthesizer. Aside from John Foxx-era Ultravox, Renner’s process was inspired by the period’s electronic pioneers venturing into deeper, romantic pop pastures, like Bill Nelson and The Associates. Apart from his writing, Renner explored music as a complement to visual language: many of the dream-like instrumental passages presented across Few Traces were originally implemented as sound elements for exhibitions of his paintings. Compiled three decades after the music was originally put to tape, Few Traces collects Mark Renner’s early music but strives not to simplify or reframe it. Mark is still an active musician and painter. The instrumental explorations remain on par with the great ambient adventurers of the period (Brian Eno, Harold Budd, Roedelius), while the vocal and guitar-centric songs transverse similar terrains to contemporaries like Cocteau Twins, The Chills, and The Feelies. You can purchase the compilation via RVNG Intl here.

Interview by JD Walsh (Shy Layers)

———————————————

Hey Mark.

Hey JD, where are you calling from?

Atlanta, where my home studio is. You said you’d booked some recording time in the studio the last few days, is that still what you’re up to?

Yeah, it’s an ongoing project. I started back in Baltimore in the spring of last year, and then I recorded out in the middle of a field in a trailer this summer, went to Glasgow in November, and then back again to northern Texas, where I am now. The great thing about this setup is that I can enlist the help of other musicians: a few other guitarists, a fellow by the name of Jared Flynn in Baltimore, and Julius Fischer, who’s a music minister in a Baltimore church. He’s a great arranger and pianist, and he plays guitar and saxophone and a few other instruments. Then in Glasgow I got to work with Malcolm Lindsay, who does film soundtracks and composes for orchestra and opera, so I had a wonderful experience reconfiguring and reworking with him. He discarded just about everything from the demos I gave him, just using the structures of the songs.

And after your work’s been arranged and rearranged by collaborators, it must be thrilling to get it back and see what they’ve brought to it.

It’s a great honor to have people even listen to your work, but to have them rethink it without disturbing your original framework, that’s really a pleasure, particularly with Malcolm. He’s a very gifted individual.

You said you had an art studio as well and you work on both—do you find it’s easy to work on music and art simultaneously, or do you need to immerse yourself in one or the other?

Years ago somebody asked me about this. At the time it was like having a jealous wife—if you spend too much time working on one thing, you feel a sense of guilt for neglecting the other. I always take a sketchbook and a travelogue with me everywhere, and I’m the same way musically, so there’s a pull and tug. Luckily now I can do both full-time. I have a visual exhibition of my paintings that I’m working on right now for the end of June, and that’s a looming deadline. The override would probably be my visual work, because I’ve been drawing since I was two or three, my mother told me, and because I approach music in a similar manner as I do color and impression. In the same way as with sketchbooks, I use an app on my phone to jot down song ideas. In the late 80s and early 90s I would call my house and sing an idea over the answering machine. (laughs) I also had one of those little—I don’t know how old you are, if you remember microcassettes? Those were good for that. I don’t know if you had a chance to listen to anything off the last few recordings—

I did.

There are quite a few elegies on Goldenacre. There’s a song called “At The Far Side of the Sea,” which is a true story about two of my high school friends. The three of us made all these nomadic, romantic plans to travel adventurously, build boats and sail around the world, but one of them kind of spiraled downward from the time we graduated high school until he eventually took his own life. He went out on his front lawn and set himself on fire. I don’t know if knowing that makes it easier to relate to the lyrics, or if it accurately did justice to him. At this age a lot of the lyrics I write are intended to be elegies to people I’ve known who have touched me. There are three or four of them on Goldenacre, a couple on Enduring The Going Hence, and the album I’m currently recording has quite a few as well.

When you have something as vivid as that, do the words exist before there’s a piece of music set to it? What’s your process when turning something on the page into the song?

Some visual artists dream their work. Most of my visual work comes from my imagination, but some are things that I come in contact with visually. One of my favorite things is hearing people express themselves, like in a museum or out in the world. I love dropping vocal sound bites into instrumental pieces. You can extract something deeply profound or poetic from things you picked up in conversation. Sometimes it’s a turn of phrase that might be vanishing from our cultural vocabulary. When it was raining, my grandfather used to say, “It’s not fit for man or beast out there.”

Right, I do the same thing, taking notes and phrases like that. But I normally start with a piece of music and try to retrofit lyrics over the melody. I’m interested in what it’s like to approach it the opposite way, starting with something that exists on the page, divorced from a musical context.

Sometimes you’re fortunate to be given a really good melody, and you’re fortunate enough to have the microcassette or the phone next to you so you can put it down. I’ve wondered about musicians like Leonard Cohen, Brian Wilson, or Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout—such great song crafters, to be able to turn you any way they want with the melody or the structure of the song. If I had to get more analytical, I would say act quickly before your idea vanishes.

Yeah, it’s really hard to distill process down to a sound bite. But back to Few Traces, I was looking through the insert that comes in the LP, the text by Brandon Soderberg about The Lost Years exhibition—how it was a literal combination of visual art and music. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I don’t know if you’re familiar with Baltimore—being a port town, it has a harbor along the Potomac, with an older section of buildings that date from the 1800s, some even earlier. It was kind of a sailor’s paradise, an unloading point. Anyway, I had an opportunity to do an exhibition at a gallery there, and I think it was shortly after I had just gotten my first 4-track and was thinking about the idea of combining the two mediums. My knowledge of the art world wasn’t very broad at the time, which was helpful because I wasn’t intimidated. (laughs) At the time the Walkman cassette player was everywhere, and I thought, what if rather than blasting the music in the gallery I just made it portable so people could drop it in a Walkman and walk around and view the work? That’s why the pieces from The Lost Years were meant to be brief, because you didn’t want to have to stand in front of the piece for too long, waiting for something that would never happen and might not be able to deliver.

So it wasn’t one piece of music per painting? They were free to look at the different paintings with whatever was on the Walkman at the time?

Yeah. Some of the titles overlapped, but it didn’t have to be strictly adhered to song-by-painting. There was a freedom to traverse the gallery.

That sounds like a fun process. Sound in a gallery is tough, and it gets tougher if you want to localize sound so there can be multiple elements happening at the same time, so I thought that was a clever solution. With regards to Few Traces, how does it feel to see so many years of work in one collection? Do you feel as if it gives you perspective, to see it all in one place?

The reception has been great and overwhelming. As an artist, you know that there’s no greater honor than to have someone invest in your work, to be able to understand it. I think Jean Cocteau said he wanted “not to be marveled at but to be believed.” One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned in the process is to take care of your archives! A lot of things escaped this particular package that must still exist somewhere, but I haven’t been able to track them down. A lot of those pieces I haven’t heard in many years, not since they were mastered. Some of them were recorded on a 4-track cassette recorder without compression, so they have an ancient archeological charm to it. (laughs) Matt was very patient, and he really extended himself waiting for me to get it all together. I made a few different trips back to Baltimore to sort through all the work—I had a house there, so I wanted to see if I could locate some of the recordings, and I contacted a few people I used to know to locate videotapes. Mostly I wasn’t successful. What Matt put together mirrors what survived. It’s a great honor, to see that stuff that I sat in a little row house and composed at my kitchen table and never thought it would be of much interest to anyone. Hopefully it can be encouraging to someone too, now that even better, more affordable technology is available—that nothing should stop you from trying.

I completely agree, it’s wonderful. I’ve seen this in the video world as well. In some cases the so-called professionals have some fears, like, “Here comes everybody with their cheap technology, invading our precious space,” but I sort of welcome it. If there’s an easier, more obtainable way for someone to do something creative, I say go for it.

Right, you can’t really have an elitist attitude about it. It’s funny, sometimes I’ll listen to something and think, “Man, I spent two hours trying to play that by hand, and now you can program it into a sequencer so quickly…” (laughs)

Right, and quantize everything, ha! Well, thank you very, very much—I’m such a fan, and I love the collection. I’m excited to see your new work, and I love your visual work as well, so good luck on the exhibition coming up!

That means a lot, thank you.

———————————————

Thanks to Mark Renner, JD Walsh, Matt Werth, Brandon Sanchez, and RVNG Intl.

for facilitating this interview. Text has been condensed and edited for clarity.