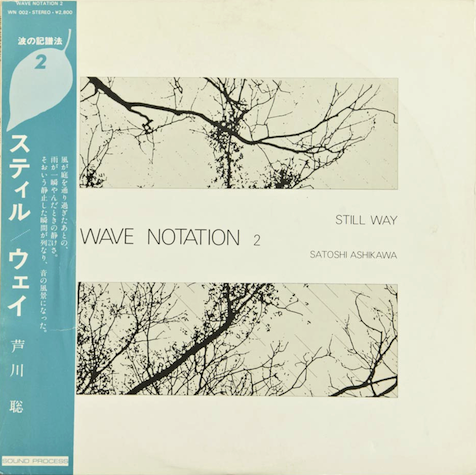

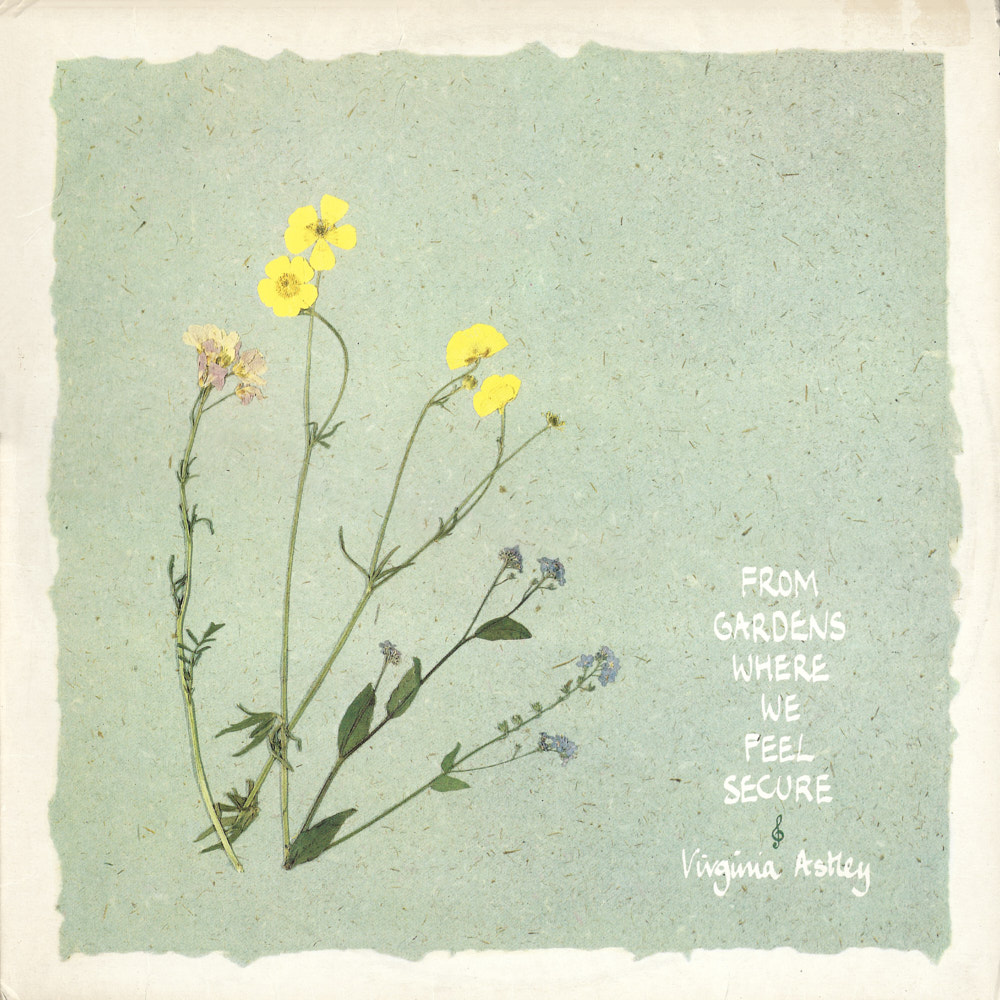

Convenient that I realized that I hadn’t yet posted Virginia Astley’s debut full-length, From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, on Easter Sunday, of all days (though I did share her very important Hope in a Darkened Heart a few years back). While From Gardens is a squarely summer record–suggesting from all angles the soporific heat of peak July–it is about as pastoral as music can possibly be, which means it’s a record that I start reaching for at the first signs of spring. Alongside Claire Hamill’s Voices, it paints a picture of a heavily romanticized ideal of the British countryside, refracted through childhood memories and the heavy lethargy of summer. Both the album title and the track title for “Out On The Lawn I Lie in Bed” are taken from W.H. Auden’s 1933 poem “A Summer Night,” and fittingly From Gardens recreates the experience of a summer day in its entirety in chronological sequence, with the A side titled “Morning” and the B side “Afternoon.”

It’s languorous, unhurried, and arguably a true ambient record in how well-suited it is as background music, something which Astley herself pointed out in a radio interview: “Whoever’s listening could lie down and put it on, and not really listen to it that much. Just have it on in the background.” Songs aren’t structured like songs so much as curiosity-driven variations on motifs–it’s easy to imagine Astley arriving at a piano refrain that she found particularly pretty, and playing with it until organically arriving at the next “song”–all of which flow seamlessly into one another uninterrupted, just like the experience of a particularly hot day.

More specifically, in addition to being a true ambient record, it’s a freak outlier in how nakedly beautiful and fully realized it is, especially for its time. As Simon Reynolds details here, there was no culture for music like this in 1983. Britain was in the thralls of post-punk and post-post-punk, with sounds going in thousands of different and gritty directions but certainly not backwards, and it’s easy to imagine detractors calling From Gardens just that–regressive, anti-avant-garde. There was something very brave about structuring an entire record around nostalgia and what is very legibly a deep love for bucolic Britain, referencing romanticism and Auden and a lifestyle that it’s difficult for me to imagine as anything other than aristocratic. Yet while Astley was classically trained, From Gardens was clearly informed by a vision that was very novel and fully her own: her personal field recordings made in the village of Moulsford-on-Thames, spun together with luminous piano, flute, and xylophone melodies, with small and elegant hints of electronic manipulation: church bells that chime forever, glitchy manipulation in “When The Fields Were On Fire,” the looping sound of a creaky swing swing gate* forming a pseudo-percussive backbone in “Out On the Lawn I Lie In Bed.” Astley is honest in her nostalgia for something which no longer exists, and she knowingly depicts it in an overly-perfect, hyperreal way that suggests it may have actually never existed at all. But it’s all hers, from start to finish: Astley wrote, recorded, and co-produced From Gardens herself, but moreover she saw the gardens, remembered them, and reimagined them in a way that no one else could. Happy spring–I hope you enjoy.

*I incorrectly heard that sample as a swing, but since Astley very considerately labeled and time/location-stamped all her samples, I’m happy to report that it’s a gate!