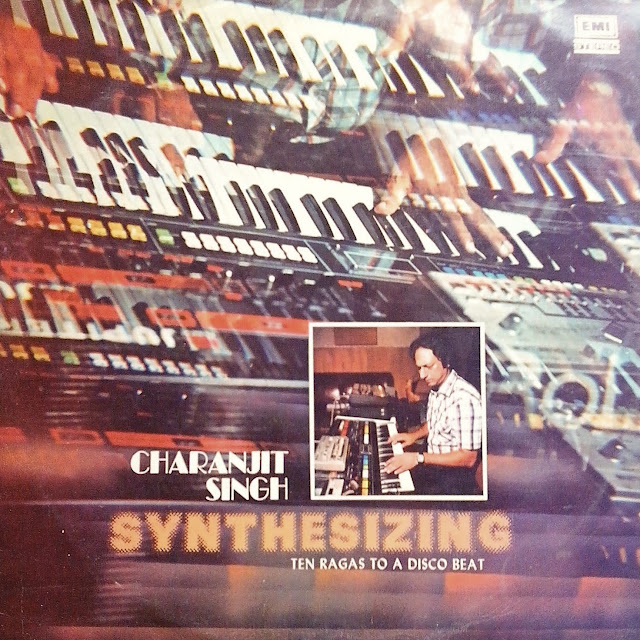

We were deeply saddened to learn that Indian musician Charanjit Singh suddenly passed away at home in Mumbai this morning, at 75 years old. His death came just a few months after the passing of his wife, Suparna Singh.

Over the past few years, Singh’s story has been told hundreds of times, attaining mythological status. It started as whispers on the internet in 2005, rumors of a record of frenetic acid house renditions of traditional Indian ragas–but it was the record’s release date that left listeners in disbelief. Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco beat was purportedly recorded in 1982, a full three years before Phuture wrote “Acid Tracks,” generally acknowledged as the pioneering acid house track.

It took another five years for Synthesizing to be reissued, instantly cementing it as an electronic cult classic. Singh surfaced and started playing shows, largely thanks to the efforts of Rana Ghose. With Singh’s reappearance we learned that he had been a Bollywood session guitarist, that he had bought his Roland TB-303 in Singapore shortly after its introduction in late 1981, and that Synthesizing had come about through at-home experimentation. Singh recounted:

There was lots of disco music in films back in 1982, so I thought, why not do something different using disco music only. I got an idea to play all the Indian ragas and give the beat a disco beat–and turn off the tabla. And I did it! And it turned out good.

We were fortunate enough to have Charanjit play at Body Actualized Center last August (photos below) and it was one of the most memorable musical experiences of our lives. The show was packed and sweaty, with Charanjit shredding through a long and ecstatic set on his Jupiter 8 in a suit jacket, unfazed by the heat. As was their tradition, his wife Suparna was seated next to him smiling the entire time.